STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) education is often credited as the driving force of modern society’s technological progression. However, there is one element that still hinders innovation: the gender gap.

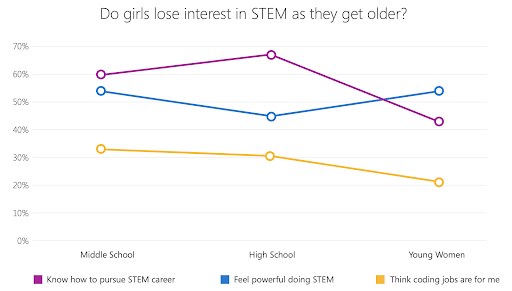

One leading American technology corporation has been at the forefront of providing STEM education opportunities for women. In their 2018 study, “Closing the STEM Gap,” [1] which used the combined data from 6,000 American girls and young women, Microsoft found that around 31 percent of middle school girls disagree with the statement, “[I] think coding jobs are for me.” Once enrolled in high school, almost 10 percent more of girls agree. Most strikingly, this percentage increases by 18, a whopping total of 58 percent, when requesting input from adolescent women who attend college, “ironically, the ones who are closest in their lives to starting a career.”

When compared to adolescent women, it turned out that it was actually middle school girls who felt most encouraged about pursuing coding jobs. At this stage in schooling, educators have the most potential to impact these girls’ attitudes toward STEM fields. They have the chance to make a significant difference in girls’ future participation throughout their high school career and beyond. However, when prompted with the statement, “[I] feel powerful doing STEM,” there was an evident decline in agreements from middle school to high school girls.

Reasons for early stages of discouragement among girls vary. The most common explanations link to being compared to boys in the classroom or at home, immature misconceptions that girls who participate in STEM are “nerds,” and that there is no active encouragement by teachers and parents inspiring girls to explore these avenues.

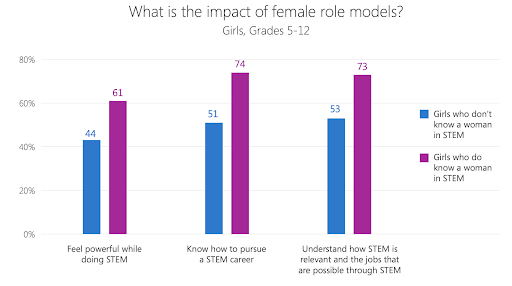

One way to counteract this loss of confidence among girls and re-spark interest in STEM would be to expose young girls to female role models in STEM fields. Specifically, perceptible representation is key to inspiring girls to practice STEM. Girls in grades 5-12 who can name or picture a woman involved in STEM are almost 20 percent more likely to “feel powerful while doing STEM [activities].” They are also 20 percent more likely to “understand how STEM is relevant and [discover] the jobs that are possible through STEM.”

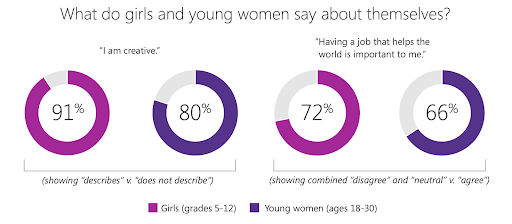

These girls fall short in understanding the correlation between creativity and values with STEM work.

Here, 91 percent of girls in grades 5-12 agree with the statement that “I am creative.” An additional 72 percent of them attest that “Having a job that helps the world is important to me.” While recognizing their true capabilities and ambitions is a step closer to immersing themselves in the world of STEM, the data shows that these girls fall short in understanding the correlation between creativity and values with STEM work.

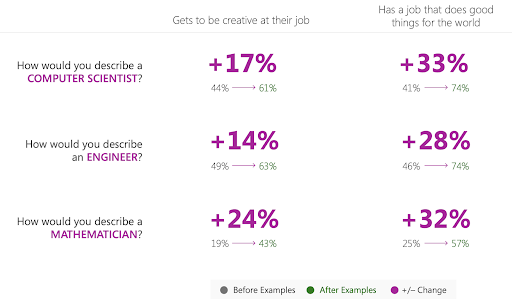

This is where real-world applications of STEM must take place. Microsoft asked the middle and high school girls whether computer scientists, engineers, and mathematicians “[Have] a job that does good things for the world.” Given the girls’ lack of knowledge on the types of occupations in STEM, 54 percent or less disagreed with each of the three prompts. Interestingly, more than 70 percent of the girls believed that mathematicians have a job that does not advance or help the world in any way. Following the shocking responses, Microsoft provided the girls surveyed with brief descriptions of actual accomplishments of engineers, mathematicians, and computer scientists to evaluate their change of perceptions. When revisiting the question, the girls’ responses doubled in acknowledgment of the occupations’ moral successes.

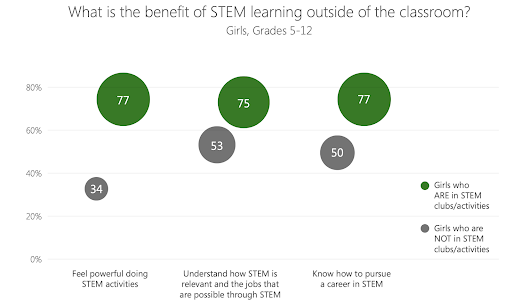

Furthermore, an integral part of regaining girls’ interest in STEM is to offer new learning opportunities through extracurricular activities. These may take the form of STEM clubs, exclusively for girls, so that educators can devote their full attention to creating hands-on, practical activities or experiments. Microsoft researchers support that additional access to STEM and computer science endeavors outside of the classroom is necessary; they note that, of the middle school and high school girls who only encounter STEM inside the classroom, only 34 percent of them “feel powerful doing STEM activities.” With further interaction with science, math, and technology outside of school, 77 percent of the girls indicate that they feel empowered by their hands-on experience in STEM activities.

Simply joining coding, robotics, engineering, or math clubs, for example, middle school and high school girls tend to feel more confident in their STEM studies, as well as feel more committed to their future studies. “Middle school girls who participate in STEM clubs and activities are more than twice as likely to say they’ll study physics in high school, and nearly 3 times as likely to say they’ll study engineering. At the high school level, girls participating in STEM clubs and activities are over 2.5 times more likely to say they’ll continue studying computer science in college.”

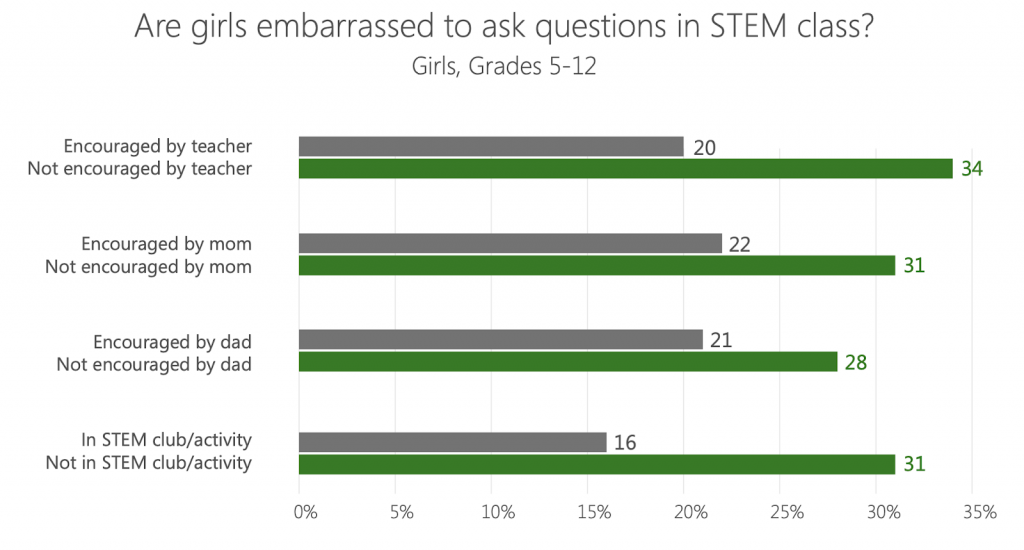

Thirty-four percent of middle school and high school girls admit that they are embarrassed to ask questions in STEM-related classes.

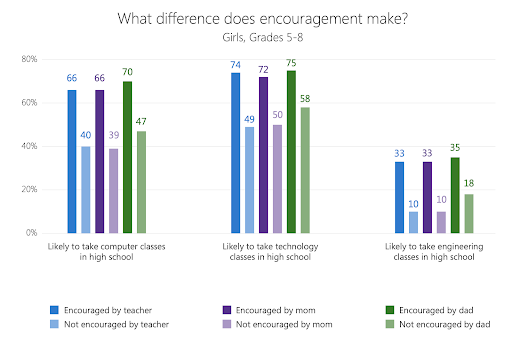

Lastly, it is essential that girls in middle school have concrete motivators. Parents, teachers, and even social media platforms can take on the role of a motivator. Microsoft found that girls from grades 5-8 who are encouraged by their teacher, mother, or father, were 20 percent more likely to take computer, technology, and engineering classes in high school. Notably, girls who were explicitly supported by their fathers have a higher likelihood of continuing STEM classes in high school. This may stem from the common conjecture, often purported by popular media, that successful figures in STEM fields are traditionally men. Therefore, hearing positive feedback from a paternal figure in their lives pushing them to study STEM courses helps girls realize that there is a much-needed place for them in the world of STEM. Specifically, STEM and computer science teachers play a fundamental role in making girls more comfortable to share their ideas in their classroom. Thirty-four percent of middle school and high school girls admit that they are embarrassed to ask questions in STEM-related classes. When encouraged by a teacher, that rate drops to 20 percent.

“The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts that technology professionals will experience the highest-growth in job numbers between now and 2030. Failing to bring the minds and perspectives of half the population to STEM and computer science fields stifles innovation and makes it less likely that we can solve today’s social challenges at scale,” states Dr. Shalini Kesar, Associate Professor in the Department of Computer Science & Information Systems at Southern Utah University and Microsoft “Closing the STEM Gap” study collaborator. Through these kinds of studies, it soon becomes apparent to educators and STEM corporations alike that the female leaders, innovators, and trailblazers of tomorrow are made in today’s classrooms.